October 28, 2010

By James Churchill

Fresh cutovers have always been underrated whitetail magnets.

By James Churchill

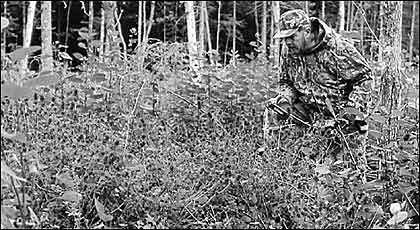

When pre-scouting a cut, look for corridors that deer use while negotiating the maze of branches and tops left after the logging operation. |

Last year, I kept close track of the deer migration into a 120-acre timber sale in our hunting grounds. This area customarily has about 15 to 20 deer to the square mile, so there were probably a half dozen or fewer deer living in the sale when the cutting started. A week later, I saw herds of five or more, in a month there was a herd of 20 to 30 feeding in one place, at one time. Eventually, 50 to 75 deer moved in. The abundance of food lying on the ground drew in most every deer within hearing distance of the noise made by the chain saws.

Such deer concentrations can, of course, offer excellent hunting. My friend, Tamarack, and I had one of the best late-season, antlerless hunts possible in a large, recently completed logging operation. We developed the opportunity by calling the office of Champion International Corporation in northern Michigan. The forester in charge of the work told us the logging crew would be moving out soon, and we were free to hunt it after they left.

Advertisement

The weekend before we intended to hunt, we scouted the sale, found an incredible amount of deer tracks, picked out stands and built blinds from the abundant slash lying on the ground. I had hardly settled in my blind the first morning when a herd of six deer, walking in single file came down the trail I was guarding. There were two large does in the group, but neither offered a shot, so I just relaxed and enjoyed the parade. A few minutes later, three deer walked by and then another herd of five assorted animals, including two small bucks.

I didn't loose an arrow the first day. Tamarack shot a yearling, purposely passing up several larger animals. The second day was much quieter, but just before quitting time I saw a pair of big ears over the treetops near my blind. I grabbed my bow and prepared myself to shoot. When the doe was clear of all obstructions, I released the arrow. She was excellent eating, and by shooting antlerless animals we had benefited the sex ratio imbalance of the deer herd.

Advertisement

Of course, hunting for a big buck in a cutover area is another matter completely. Most every big buck residing anywhere near road access has survived several attempts on his life. He will be very watchful and wary and will probably spook at the slightest hint of danger.

Bowhunters working cutover areas harvest wallhangers for the meat pole every year. I got one that probably just moved into the cutting the day I shot him. I was sitting in a tree stand in northern Wisconsin one bitterly cold afternoon. Although dressed for the conditions, the cold slowly seeped through, and I was starting to shiver. I thought about quitting, but the afternoon sun was almost to the tree line. After wavering several times, I finally decided to tough it out until the shooting hours were over.

Be sure to build your blind on trails leading to the cut unless you are trying to ambush deer that are up and feeding. |

It was a good thing I did. I waited for another half-hour and was just about to stand up to descend the tree when I heard the loud crunch of a heavy animal walking in the snow. The sound was coming down the trail towards me and in an instant all the chill was gone as I saw the deer. It was a high-tined, heavy -bodied eight-point buck, and he was walking right into my shooting lane.

I had to pluck the bow from its holder, adjust the arrow on its rest and draw, but later I had no memory of this action. I do recall the arrow flying exactly where I aimed, the deer running a few steps forward, then whirling and running back the way it came. My son and I found him the next morning, about 100 yards away.

As most hunters know, scent and noise will alert wary bucks that inhabit cuts, but if they actually sight you they might run for a mile or more and completely abandon the hunting area. Last year, I saw this played out in no indefinite terms.

A big buck was using a large, crescent-shaped timber sale that I was hunting and I had moved my tree stand around to three different locations to try and intercept him. On two occasions, I saw him, about the same time as he winded me. He didn't appear unduly disturbed; he just changed his route to avoid the danger. The next day his huge tracks would be imprinted over his previous route, an indication that he wasn't too alarmed. He was probably accustomed to human scent and sounds from the logging operation that was recently completed.

One afternoon, I was late getting to my hunting area; a previously selected tree stand located at the edge of the cut. I was hurrying, and threw caution to the wind. Just as I rounded a corner in a logging road, I encountered a heavy-bodied, big-racked buck walking in my direction. He was only about 15 yards away, and we stared at each other in shocked surprise for a millisecond. Then, he whirled and became a streak of gray and white as he sped back down the road for a few rods, turned, leaped a snow-covered treetop and vanished.

The next day, I followed his tracks for about a mile before he stopped running, and for another hour after he started walking, and he never stopped or laid down. He was clearly migrating completely away from the feeding area he had been using. I never saw him or even his track again.

Since then, we have developed some proven, intensive procedures to avoid being seen. First, we take a tip from the buck himself, and use whatever cover is available to approach your stand. Never cross an opening if you can avoid it. Move slowly; wear full camouflage, even a facemask. If you must cross an opening, bend from the waist as much as possible to look less like human.

The described strategy certainly helps the hunter get in place when hunting newly-fallen trees. Consider also that logging operations do a lot more for deer than supply freshly severed tree limbs. After the first winter snow melts and the next growing season starts, the roots of the cut off aspen and maple will sprout new shoots. They grow rapidly and soon will reach upwards to three feet or more and leaf out.

A season or two after a new cut will allow tender new growths to reach three feet high or higher. This provides a great food source for bucks and does alike while providing adequate cover for a slow stalk. |

Tree leaves, aspen leaves in particular, will attract deer, even big bucks, like water attracts ducks. In almost every large cutover area a mature buck or two, maybe even a wallhanger, will be utilizing their share of the new leaves. Further, grass and forbs that grow up in the new opening make the cut additionally attractive.

When the fall hunting season arrives, find a buck's feeding grounds by looking for big deer tracks, rubs and scrapes. The rubs, where deer have rubbed the bark from saplings with their antlers, usually show up by early bow season in the brush that grows on the fringes of the cuts. The scrapes are made by a rutting buck pawing out bare places in the soil. They might initially appear in late October on logging roads right in the cuts.

After a big buck is found, look for a location for a stand between the cutover area, and the nearest thick stand of evergreens that might be a good bedding area. I bagged one of my first bucks in a cutover section by utilizing this concept. I happened across a large buck scrape in the interior of an aspen cutting one October afternoon. The fan-shaped patch of pawed up dirt would have covered a hunting jacket, and a footprint as wide as three gloved fingers signed it.

I scouted the area until I found a place where a logging road was bulldozed through a low ridge. The yard-high sides of the roadbed funneled deer directly down the logging road for a few rods. At the bottom of the ridge, a stand of good-sized white pine surrounded by thick balsam looked like a possible bedding area.

The next day, I humped up a tree overlooking the cut and got ready to shoot by mid-afternoon. Eventually, a lone fawn meandered down the trail, feeding sporadically on trailside mushrooms. I expected his mother to follow, and so wasn't really prepared when a deer stalked briskly out of the balsams on the edge of the cut. The phantom deer broke into a trot on the upslope and was out of range before I could get ready to shoot. It had six noticeable antler points.

The next evening, I saw the buck I was really hunting. Although, I was ready to shoot and focused on the trail where I saw the six-point the day before, I happened to look behind me. There, down the slope, across a logging road, a football field distance away, was a brawny, heavy-antlered buck that looked to have 10 points. He had high tines, and spreading main beams and a haughty, regal bearing. It was a buck to make your heart beat fast, but he was far out of range, downwind, and looking directly at me.

I froze in an awkward, twisted position and tried to keep from moving, hoping he would come my way. He watched for awhile and then turned and seemed to be heading for the scrape. Trying to climb down from the tree to intercept him without making noise was out of the question, so I just stayed alert in case he came my way. He didn't. A week later, I saw him again for the last time. He was walking away. I eventually got the six point, however, and learned a lot about hunting cutover areas in the process.

There are some special problems in hunting cuts. For instance, the prevailing wind direction is upset by openings surrounded by tall trees. Wind currents that have been blowing steadily across the treetops suddenly lose their support when they encounter the opening. They tumble downward and create eddies that might carry the man scent in any direction. For that reason, some cuts are nearly impossible to hunt successfully from stands placed in the opening. They are best hunted from the undisturbed timber on the fringes of the openings. If, for various reasons, you must place a stand in the cut, use a wind finder to study the direction the air currents take. Then set up accordingly.

Cutover areas evolve through three stages of growth. The first stage is when the small limber shoots are the prevalent vegetation, providing the most food and are the most attractive. Deer sometimes bed down in the new growth, but it doesn't provide much cover for an approaching hunter. This stage can be hunted by setting up on trails entering the cut. It also can be successfully worked by setting up on the downwind edge and waiting for feeding deer to eventually work their way towards you.

The second stage, when the saplings are up to six feet high and thick enough so deer will partially follow trails, are a little easier to hunt. They begin to let down their guard when surrounded by such an abundance of cover. Besides stand hunting, this stage can provide an opportunity for a stalk. Sometimes, deer rise out of their bed and stare for a minute or two at a hunter moving slowly and quietly upwind through their territory. If there is an opening, slowly draw, aim and shoot.

The third stage is when the trees are up to 12 feet high. They still provide excellent cover, but food production is declining. The leaves and twigs are more sparse and difficult for the deer to reach and deer use is diminished. The cut still might provide excellent hunting in severe weather because the dense cover will offer excellent protection to the deer. Set up in ground blinds in the interior of the cut or on runways entering the cut.

There will be thousands of deer-filled timber cuts available in the northern regions this fall. Scout for them by listening for the sounds of chain saws, watching for log piles or logging trucks. Pay special attention to where the trucks turn from the main highway, or you can contact county, state, federal or private land foresters. The local DNR office or county agent should be able to supply further contacts. Then there are, of course, the ubiquitous internet web pages. Most every official agency has one at present. Good luck.